Esquemas anatómicos

Anatomy drawings

Autora: Irene GONZÁLEZ HERNANDO irgonzal@ucm.es

Palabras clave: anatomía; ciencia; medicina; disección; universidad.

Keywords: anatomy; science; medicine; dissection; university

Fecha de realización de la entrada: 2014

Cómo citar esta entrada: GONZÁLEZ HERNANDO, Irene (2014): "Esquemas anatómicos", Base de datos digital de Iconografía Medieval. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. En línea: https://www.ucm.es/bdiconografiamedieval/esquemas-anatomicos

© Texto bajo licencia Creative Commons "Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International" (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

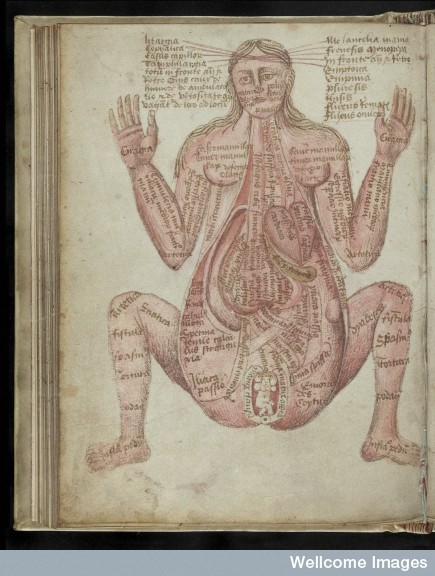

Pseudo Galeno, origen inglés, mediados del siglo XV. Londres, Wellcome Library, Ms. 290, fol. 52v (el cuerpo de la gestante y la formación del feto).

Abstract

In the Middle Ages, the schematic depiction of the human body with its inner organs for medical purposes, was linked to the consolidation of the learning and the practice of dissection in the universities. This is the reason why there are no such representations registered before the 13th century. Initially, they appeared as illustrations in medical manuscripts, closely related to the written text but, later on, three-dimensional anatomic models reached momentum. A good example is the collection of ivory detachable pregnant bodies made in the 17th century and kept in the Wellcome Library of London. This iconographical typology spread across Occident because it helped understanding the structure of the human body and allowed the incorporation of the new medical developments up to the present day.

Resumen

La representación esquemática del cuerpo humano con fines médicos estuvo ligada en la Edad Media a consolidación del aprendizaje universitario y de la práctica de la disección. Es por ello que hasta el siglo XIII no se realizaron este tipo de representaciones. Inicialmente, fueron ejecutadas en soporte pictórico, generalmente formando parte de manuscritos médicos y en estrecha relación con el texto escrito que acompañaban. Sin embargo, a medida que se produjo el paso a la Edad Moderna, se generalizaron también las representaciones en soporte escultórico, como es el caso de las gestantes desmontables en marfil de la Wellcome Library (siglo XVII), teniendo estas mucha fortuna ya que permitían ver y comprender en tres dimensiones la estructura del cuerpo humano. La proyección de este tipo iconográfico llega hasta nuestros días, ya que de la mano de los cambios médicos se han ido difundiendo esquemas anatómicos acordes a las novedades y descubrimientos.

Selección de obras

- Miscelánea Médica, origen inglés, c. 1280-1290. Bodleian Library, Oxford (Reino Unido), ms. Ashmole 399, fol. 13v (aparato reproductor femenino), fols. 14r, 14v, y 15r (posiciones fetales) y fol. 24v (aparato reproductor masculino).

- Alberto Magno, De animalibus, siglo XIV. París, BnF, Ms. Lat. 16169, fol. 59v (examen de un cuerpo masculino) y fol. 134r (anatomía de un parto múltiple).

- Johns Arderne, Chirurgica, siglo XIV. Bethseda (EEUU), National Library of Medicine, ms. 9, fol. 12 (anatomía del útero: las celdas uterinas).

- Miscelánea que incluye el Apocalipsis, el Ars Moriendi y textos médicos y científicos, origen alemán, c. 1420-1430. Londres, Wellcome Library, Ms. 49, fol. 35v (el cuerpo masculino, el útero femenino y la formación del feto) y fol. 38r (la anatomía de la gestante y al formación del feto).

- Esquema anatómico de mujer gestante,siglo XV, Biblioteca de Leipzig (Alemania).

- Pseudo Galeno, origen inglés, mediados del siglo XV. Londres, Wellcome Library, Ms. 290, fol. 52v (el cuerpo de la gestante y la formación del feto).

- Johannes de Ketham, Compendio de Medicina (Fasciculus Medicinae),1491, traducción al castellano e impresión en Pamplona (1495). Madrid, RAH, Inc. San Román 18, fol. 38 (anatomía de la mujer).

- Gestantes desmontables, escultura en marfil, siglo XVII. Londres, Wellcome Libray, nº inv. 127699 y 642631.

Bibliografía básica

ÁLVAREZ DE MORALES RUIZ MATAS, Camilo (1990): “El cuerpo humano en la medicina árabe medieval: Consideraciones generales sobre la anatomía”. En: GARCÍA SÁNCHEZ, Expiración (coord.): Ciencias de la naturaleza en Al-Andalus: textos y estudios. Escuela de Estudios Árabes, Granada, vol. 5, pp. 121-136.

CORNER, George W. (1927): Anatomical Texts of the Earlier Middle Ages. Carnegie Institution, Washington D.C.

DUMESNIL, René (1935): Histoire illustrée de la médecine. Plon, París.

HUARD, Pierre; IMBAULT-HUART, María José (1980): André Vésale, iconographie anatomique (fabrica, epitome, tabulae sex). Roger Dacosta, París.

IMBAULT-HUART, Maria José (1983): La Médecine au Moyen Âge à travers les manuscrits de la Bibliothèque Nationale. Éditions de la Porte Verte, París.

LIND, Levi Robert (1974): Studies in Pre-Vesalian Anatomy: Biography, Translations, Documents. Philadelphia.

LORBLANCHET, Hélène; TODESCHINI, Pascaline; CHAUDOREILLE, Florence (2012): La plume et le bistouri. Étudier la médecine à Montpellier au Moyen Âge et à la Renaissance, catálogo de la exposición. Montpellier.

LYONS, Albert S.; PETRUCELLI, Joseph (1978): Medicine: an illustrated History. Nueva York, Harry N. Abrams.

MACKINNEY, Loren C. (1965): Medical Illustrations in Medieval Manuscripts. University of California Press, Berkeley.

PERSAUD, T.V.N. (1948): Early History of Human Anatomy. Thomas, Springfield, Thomas, vol. II.

POUCHELLE, Marie-Christine (1983): Corps et chirurgie à l’apogée du Moyen Âge: savoir et imaginaire du corps chez Henri de Mondeville, chirurgien de Philippe le Bel. Flammarion, París.

PRIORESCHI, Plinio (2006): “Anatomy In Medieval Islam”, Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine, vol. 5, pp. 2-6.

ROBERTS, K.B.; TOMLINSON, J.D.W. (1992): Fabric of the Body: European Traditions of Anatomical Illustration. Clarendon, Oxford.

SINGER, Charles (1915): “A Thirteenth-Century Drawing of the Anatomy of the Uterus and Adnexa”, Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, nº 9, pp. 43-47.

VIAL, Mireille (dir.) (2011): Scriptor et medicus: La médecine dans les manuscrits de la Bibliothèque Interuniversitaire de Montpellier.Bibliothèque Interuniversitaire de Montpellier, Montpellier [DVD].